My DSLR, long lens, tripod totting, friend Paul and I spent several days photographing side by side in the Rio Grande Valley of south Texas. He shoots, much of the time, with his massive 400mm, f2.8 Canon Image Stabilized lens mounted on his 5D full frame DSLR and a heavy-duty carbon fiber tripod. It is a brilliant lens and a very capable camera, and he gets stunning results. However he found a few things to envy in my long zoom Point and Shoot rig (I was shooting with the Sony HX400V, 50x, 20mp camera.)

Of course I was shooting my first images while he was still setting up his tripod, and, of course, I had 4 times the reach he had…with 1200mm equivalent field of view. And of course, as the days wore on it became obvious which of us was carrying 8 pounds of lens…close to 12 pounds total equipment, and which could tuck his whole rig into a small bag at his waist. 🙂

But the thing Paul kept coming back to when we looked at our images later in the day was how much depth of field the small sensor camera gives you when compared to his full sized sensor…and most of the time he was comparing his depth at 400mm and mine at 1200mm. By depth of field, if you are not familiar with the term, I mean how much of the image, from foreground to background, is apparently in focus and sharp. For birds, wildlife, and macro work the depth of field can be critical, especially at the longer focal lengths needed to fill the frame. It is especially critical when shooting a group of birds (or other critters) as in the leading photo here. Paul was not able to get the Tricolored Heron in the foreground in focus at the same time as the Black-necked Stilts in the background, even if he stopped his 400mm lens down to f5.6 or so (reducing the aperture increases depth of field). As you see, even at 1200mm equivalent field of view, the Sony managed to get all the birds in relatively good focus.

For comparison here is one of Paul’s shots with his 400mm plus 1.4x extender for 560mm. He stopped down to f10 to improve depth, and was shooting at less than half the equivalent focal length of the Sony P&S, but still did not manage to get the same group of birds in focus.

Here is another example: the Little Blue and the Snowy were separated by about 3-4 feet, yet the Sony managed to get both in focus at 1200mm equivalent and f6.3. Only a Point and Shoot superzoom is able to do that trick 🙂

It has to do with sensor size, and the real focal length of Point and Shoot camera lenses. Since the sensor in my Sony is 5.6 times smaller than the sensor in Paul’s Canon 5D, it only takes a 215mm lens to make objects (or subjects) the same size in the image as thew would be with a 1200mm lens on his camera (215×5.6=1200). More practically for comparison, when I set my zoom to 400mm to match Paul’s 400mm Canon lens, my real focal length is only 71mm. He gets the depth of field of a 400mm lens, and, while framing the same group of birds so they look the same size in the image, I get the depth of field of a 71mm lens. That is a dramatic difference. Even at my 1200mm setting (remember 215mm real focal length), I still have twice the depth of field he does with his 400mm lens. That means that even if he crops his image to match mine, I will still have significantly more depth.

Depth of field differences also come into play when shooting close your subject. This shot of a Red Saddlebags Dragonfly from 7 feet at 2400mm equivalent field of view (1200mm optical plus 2x Clear Image zoom on the Sony), would simply not be possible in any single image from a conventional DSLR and lens, unless you shot from a few inches away with a 71mm lens (and even then you would have to crop the image by a factor of 2). And believe me, getting that close to a Red Saddlebag in the field is not easy 🙂

Or consider this true macro, taken from about an inch, using the Sony HX400V at about 61mm equivalent field of view. The real focal length of the lens at that zoom is 10.9mm…which on a full frame sensor would be a fish-eye wide angle. I get as much depth of field as I need in any macro setting.

The spider is relatively isolated, but in a macro like the one that follows, depth of field is critical to the effect.

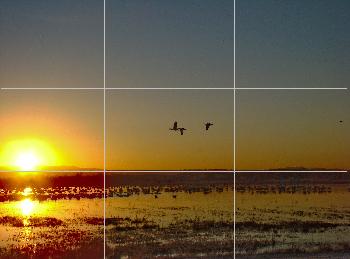

Even when shooting at wild angle, for landscapes, the extra depth of field of the P&S superzoom can be used to good advantage. I enjoy a photograph with a great depth.

It is sometimes argued that the greater depth of field in small sensor Point and Shoots is a disadvantage when you do want to use selective focus…as in some wildlife, some macro, and almost all portrait photography…where you want your subject isolated against an out of focus background for the classic photographic effect.

If I had cropped in closer by zooming out to match Paul’s 400mm, the background would have been less sharp, but not as well isolated as the full frame shot. Still, as the macros above demonstrate, subject separation can be achieved even with a P&S.

All in all, I find the extra depth of field of the P&S superzoom to be an advantage for nature photography way more often than it is a disadvantage. It makes both telephotos of wildlife and macros of bugs and flowers easier, and produces great landscape effects. In fact, I am so used to working with generous depth of field that I am pretty sure I would be quite frustrated moving to a full frame system at this point. I love shots like this one of a Common Paraque in the half-light too much. Only a P&S superzoom could produce this result…with so much of the bird in focus at this distance and scale.

So, just one more reason to enjoy Point and Shoot Nature Photography. 🙂

![compgrid[1]](https://psnp.info/psnp_/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/compgrid1.jpg)

![2156162498_64d6f9e913_m[1] 2156162498_64d6f9e913_m[1]](https://i0.wp.com/psnp.info/psnp_/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/2156162498_64d6f9e913_m1.jpg?w=265&h=199&ssl=1)

![2053278956_62b7886338_m[1] 2053278956_62b7886338_m[1]](https://i0.wp.com/psnp.info/psnp_/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/2053278956_62b7886338_m1.jpg?w=387&h=199&ssl=1)

![557235674_f1f770e6ce_m[1] 557235674_f1f770e6ce_m[1]](https://i0.wp.com/psnp.info/psnp_/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/557235674_f1f770e6ce_m1.jpg?w=326&h=245&ssl=1)

![557376619_644891c1ab_m[1] 557376619_644891c1ab_m[1]](https://i0.wp.com/psnp.info/psnp_/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/557376619_644891c1ab_m1.jpg?w=326&h=245&ssl=1)